The word "benzene" derives historically from "gum benzoin" (benzoin resin), an aromatic resin known to European pharmacists and perfumers since the 15th century as a product of southeast Asia.[11] An acidic material was derived from benzoin by sublimation, and named "flowers of benzoin", or benzoic acid. The hydrocarbon derived from benzoic acid thus acquired the name benzin, benzol, or benzene.[12] Michael Faraday first isolated and identified benzene in 1825 from the oily residue derived from the production of illuminating gas, giving it the name bicarburet of hydrogen.[13][14] In 1833, Eilhard Mitscherlich produced it by distilling benzoic acid (from gum benzoin) and lime. He gave the compound the name benzin.[15] In 1836, the French chemist Auguste Laurent named the substance "phène";[16] this word has become the root of the English word "phenol", which is hydroxylated benzene, and "phenyl", the radical formed by abstraction of a hydrogen atom (free radical H•) from benzene.

In 1845, Charles Mansfield, working under August Wilhelm von Hofmann, isolated benzene from coal tar.[18] Four years later, Mansfield began the first industrial-scale production of benzene, based on the coal-tar method.[19][20]Gradually, the sense developed among chemists that a number of substances were chemically related to benzene, comprising a diverse chemical family. In 1855, Hofmann used the word "aromatic" to designate this family relationship, after a characteristic property of many of its members.[21] In 1997, benzene was detected in deep space.[22]

Ring formula[edit]

The empirical formula for benzene was long known, but its highly polyunsaturated structure, with just one hydrogen atom for each carbon atom, was challenging to determine. Archibald Scott Couper in 1858 and Joseph Loschmidt in 1861[28] suggested possible structures that contained multiple double bonds or multiple rings, but too little evidence was then available to help chemists decide on any particular structure.

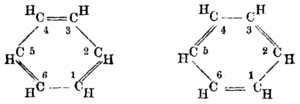

In 1865, the German chemist Friedrich August Kekulé published a paper in French (for he was then teaching in Francophone Belgium) suggesting that the structure contained a ring of six carbon atoms with alternating single and double bonds. The next year he published a much longer paper in German on the same subject.[29][30] Kekulé used evidence that had accumulated in the intervening years—namely, that there always appeared to be only one isomer of any monoderivative of benzene, and that there always appeared to be exactly three isomers of every disubstituted derivative—now understood to correspond to the ortho, meta, and para patterns of arene substitution—to argue in support of his proposed structure.[31] Kekulé's symmetrical ring could explain these curious facts, as well as benzene's 1:1 carbon-hydrogen ratio.[32]

The new understanding of benzene, and hence of all aromatic compounds, proved to be so important for both pure and applied chemistry that in 1890 the German Chemical Society organized an elaborate appreciation in Kekulé's honor, celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of his first benzene paper. Here Kekulé spoke of the creation of the theory. He said that he had discovered the ring shape of the benzene molecule after having a reverie or day-dream of a snake seizing its own tail (this is a common symbol in many ancient cultures known as the Ouroboros or Endless knot).[33] This vision, he said, came to him after years of studying the nature of carbon-carbon bonds. This was 7 years after he had solved the problem of how carbon atoms could bond to up to four other atoms at the same time. Curiously, a similar, humorous depiction of benzene had appeared in 1886 in the Berichte der Durstigen Chemischen Gesellschaft (Journal of the Thirsty Chemical Society), a parody of theBerichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, only the parody had monkeys seizing each other in a circle, rather than snakes as in Kekulé's anecdote.[34] Some historians have suggested that the parody was a lampoon of the snake anecdote, possibly already well known through oral transmission even if it had not yet appeared in print.[12] Kekulé's 1890 speech[35] in which this anecdote appeared has been translated into English.[36] If the anecdote is the memory of a real event, circumstances mentioned in the story suggest that it must have happened early in 1862.[37]

The cyclic nature of benzene was finally confirmed by the crystallographer Kathleen Lonsdale in 1929.[38][39]

Nomenclature[edit]

The German chemist Wilhelm Körner suggested the prefixes ortho-, meta-, para- to distinguish di-substituted benzene derivatives in 1867; however, he did not use the prefixes to distinguish the relative positions of the substituents on a benzene ring.[40] It was the German chemist Karl Gräbe who, in 1869, first used the prefixes ortho-, meta-, para- to denote specific relative locations of the substituents on a di-substituted aromatic ring (viz, naphthalene).[41] In 1870, the German chemist Viktor Meyer first applied Gräbe's nomenclature to benzene.[42]

Early applications[edit]

In the 19th and early-20th centuries, benzene was used as an after-shave lotion because of its pleasant smell. Prior to the 1920s, benzene was frequently used as an industrial solvent, especially for degreasing metal. As its toxicity became obvious, benzene was supplanted by other solvents, especially toluene (methyl benzene), which has similar physical properties but is not as carcinogenic.

In 1903, Ludwig Roselius popularized the use of benzene to decaffeinate coffee. This discovery led to the production of Sanka. This process was later discontinued. Benzene was historically used as a significant component in many consumer products such as Liquid Wrench, several paint strippers, rubber cements, spot removers, and other products. Manufacture of some of these benzene-containing formulations ceased in about 1950, while others continued, either as a component or a significantcontaminant until the late 1970s, when an increased incidence of leukemia was linked to Goodyear's Pliofilm production operations in Ohio.[citation needed] Until the late 1970s, many hardware stores, paint stores, and other retail outlets sold benzene in small cans, such as quart size, for general-purpose use. Many students were exposed to benzene in school and university courses while performing laboratory experiments with little or no ventilation in many cases.[citation needed] This dangerous practice has been almost eliminated.[citation needed]

Occurrence[edit]

Trace amounts of benzene are found in petroleum and coal. It is a byproduct of the incomplete combustion of many materials. For commercial use, until World War II, most benzene was obtained as a by-product of coke production (or "coke-oven light oil") for the steel industry. However, in the 1950s, increased demand for benzene, especially from the growing polymers industry, necessitated the production of benzene from petroleum. Today, most benzene comes from the petrochemical industry, with only a small fraction being produced from coal.[43]

No comments:

Post a Comment